Author Illustrates Fluidity of Racial, Religious Identity

Laura Arnold Leibman Discovers Multiracial Jewish Family That Can Trace Roots to Two Enslaved People in Barbados

Publishers Weekly ran my edited interview with author Laura Arnold Leibman about the fluidity of racial and religious identity. In the version below, there’s a little more of our discussion, including the Leibman’s feelings on critical race theory and other issues. Through her discovery of this multiracial Jewish family, many of our preconceptions of black, white, and Jewish fall by the wayside.

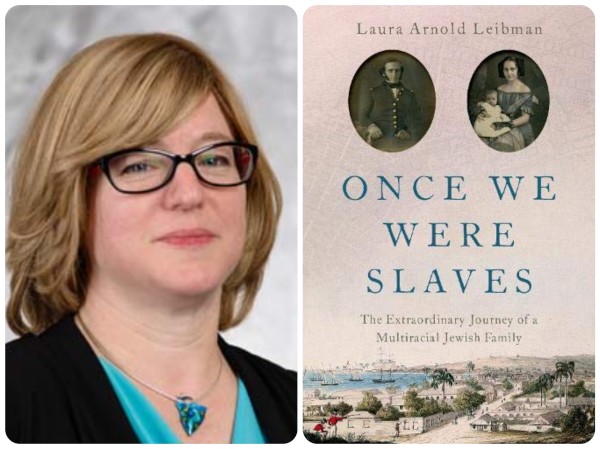

What does it mean to be Jewish? Or Black? What about both? Now, how about a black Jewish family that can trace its lineage back to two enslaved people in Barbados? This was a mystery and challenge that proved too intriguing for Reed College professor Laura Arnold Leibman to pass up. Her book, Once We Were Slaves: The Extraordinary Journey of a Multiracial Jewish Family (Oxford University) tracks a family that can trace its lineage back to Sarah and Isaac Brandon, two enslaved people in Barbados. The result is a book that sheds light not only on the past, but also can illuminate our current debates over how to make Judaism more welcoming and the fluidity of race. PW recently interviewed Leibman to learn more about how and why she wrote this very timely history book.

Tell me about your background and how you approach your work

I’ve been working in Jewish studies for a while, but my training is as an early Americanist. I’m really used to working with communities where there are few resources. That did help in terms of working in Barbados and trying to trace the history of the enslaved part of the family.

How did you first discover Sarah and Isaac Brandon?

I was in Barbados, working on the book that became Messianism, Secrecy and Mysticism: A New Interpretation of Early American Jewish Life, which came out in 2012. I was interviewing Karl Watson, who is the king of Barbadian history. He mentioned there was this interesting case involving Isaac Lopez Brandon. Later, as I found the miniatures, I was like, “Whoa, wait a second.” Suddenly, I’m so much more interested in that story because we have objects. For me, once I have the objects, then I’m really engaged in the story. It would be so much harder without some visual sense of who they are just from how they smile in their miniatures. So then it was a matter of going back and looking at the manumission records to try and figure out what had happened.

Your book is about moving from enslavement to freedom, and the fluidity of religious and racial boundaries. When you sit down to write something like this, what’s foremost in your mind

For me, this was really an opportunity to try and get at some of the lives of people of Jewish and African descent in those different places where we don’t have that wealth of information. I really did want that to be their story. But, also, how their story relates to that larger history, that’s even harder to capture because there are people who didn’t end up being freed. I do feel like the minor characters in the background, they really help fill in the “what if?” What if this had happened exactly this way? What would their lives have been like?

You’re a historian, but there are so many elements to this book that resonate today, from Jewish/African American relations to what they’re now calling Critical Race Theory. What do you want people to walk away with after reading your book?

If people see there’s been a diversity of types of Jews in the United States and in the Americas from the get-go, that would be a great revelation, just as Jewish communities today talk about how can we be more inclusive and even more welcoming. At the same time, I am interested in people thinking about how the understanding of race changed over time. That, I think, is a concrete way for people to engage with some of the aspects of Critical Race Theory that sometimes people not catching on to, which is how race is socially constructed. But just because it’s a social construct doesn’t mean that it’s something that isn’t constantly being a source that acts upon people. What gives them their agency at various points and what are they not in control of?