Private Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion

In this audio excerpt of my memoir, I am 19 years old and learn an important lesson about perception and reality in Muslim-Jewish relations; and I begin my accidental Jewish journalism career.

In this scene of my memoir-in-progress, I learn an important lesson in college about perception and reality when it comes to Muslim-Jewish relations. And I’m introduced to the infamous Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. More on that in a bit. The year is 1985, and, as I say in this excerpt, I think I know everything, when in fact I know very little. This is typical for a person who is only nineteen years old and being exposed to many things for the first time in life.

This is the story of the beginning of many things in my life: An understanding of Arab perceptions, an intense friendship I had with a Palestinian woman, my own journey through the way others perceive Judaism, and the accidental beginning of my career in Jewish journalism. The passage at the end will make sense in context, I hope. A recurring theme in my book is also my struggles with OCD and how the comfort of Jewish ritual gave it a home.

From time to time on this blog, I’ll post various excerpts as I get closer to completing my book about my grandfather’s life in pre-Holocaust Hungary, and my own personal journey through Judaism.

I decided to narrate this short chapter to see if I had the stamina to, eventually, record my own audiobook. Turns out, I’m not sure. I decided to take this seven-minute snippet and add some music to the background to make my voice perhaps sound more appealing. But, then, everybody is critical of their own voices.

You can read more excerpts from my work-in-progress on my Memoir page.

My Private Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion

For those who’d rather not hear my voice, here is the raw, unedited version of this chapter.

“You don’t know everything, Howard,” Lamya told me, her eyes rolling slightly, revealing just a hint of humor, letting me know that she was both kidding and not kidding. It was 1985 and we were both working at my college newspaper at Wayne State University in Detroit. I did not know much about her, except I heard that she was Palestinian and had escaped from an abusive marriage.

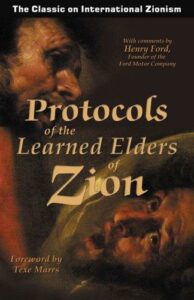

“You think you know a lot, but you don’t know everything,” she said. Well, a more accurate statement might have been that I didn’t know anything. She was thirty years old and I was only nineteen. There were a great many things I did not know, but Lamya was specifically referring to my lack of knowledge about Arab culture and the way they think about historical and current grievances. I saw this in the angry letters to the editor I was receiving over my coverage of controversy over a book, a kind of silly-looking book. Turned out, the book was not a book at all, but really a fun-house mirror through which one could view many layers of distortions.

A few days earlier, Rabbi Oppenheimer of the campus Hillel approached me at the Student Center. I don’t know how the rabbi found me, or even how he knew who I was. I had never dropped by Hillel’s area of the Student Center. Somebody must have pointed me out to him as the guy who was writing pro-Israel commentaries in the student newspaper. He didn’t look like much of a rabbi to me. He wore a Greek fisherman’s cap. Tall, scruffy-bearded, he walked with a slouch that made it appear as if he was folded in half at the waist, but the crease stayed.

We had never spoken before, yet Oppenheimer approached me as if we had known each other for years and were continuing an earlier conversation. He tossed a book near my lunch tray, shaking the gravy well in my mashed potatoes, and then hovered above me and asked, “Guess what I found the Muslim Students Association selling at Manoogian Hall?”

It wasn’t really a book. It was more like a pamphlet. On the cover were a strange combination of words that actually struck me as funny. The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. I didn’t know what to make of it. There was an undertone of what I took to be Jewish sarcasm right there in the title. It seemed like it could be the script for a new Mel Brooks movie. You know, like Jews in Space. I looked up at the rabbi with a half-grin on my face, waiting for the punch line. Instead, there was silence. It took a couple of beats for me to realize that Oppenheimer was waiting for a reaction from me. I had nothing. He let out a tiny sigh and sat down next to me.

“Surely you’ve heard of the Protocols,” Oppenheimer said.

My blank stare was his answer.

This is what Lamya was trying to tell me when she said that I did not know anything. “It doesn’t matter if the Protocols are true,” she said. “Most Arab Muslims believe they are true, so that is the reality you deal with.”

Up until then, my knowledge of anti-Semitism was narrow, despite some experience with it during my early life in Georgia, and later in a suburb of Chicago (“Hey, Howard, aren’t you going to pick up that penny?”). But the serious, deadly kind of anti-Semitism was confined primarily to the Holocaust, fed mostly by my grandfather’s stories of Hungary. What happened before the life of my grandfather, or how it fit in with the larger narrative of my people, I was clueless. That’s what it is to be truly obsessive in the clinical sense. The information you obtain, obsessively, is narrow, focused, and often incomplete because it ignores the periphery and all that comes before and after. It was akin to extreme contemplation of the chalk outline of a corpse with no knowledge of the events that led to the murder. My obsession with the Holocaust was devoid of context except my own family’s.

“The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion,” I grinned slightly. The name still sounded funny to me.

“I’ll leave this here with you,” said the rabbi, who was not smiling at all. “Read it, and then come see me at Hillel and I’ll give you a statement for your story.”

My story? I had never agreed to write a story on this. But, nevertheless, I flipped the book open and the more I read, the more curious I became. Mel Brooks indeed, It was filled with what I found to be laughable lines about One World Government under the control of International Jewry. It was obviously written by anti-Semites, but if you are a Jew who denies it was written by Jews, well, then that just proves that you are part of the plot. That’s the beauty of a conspiracy theory. The more you deny, the guiltier you seem. And, now, Arab students are using it as some kind of proof of Jewish intent in the Middle East.

This is what Lamya was trying to tell me when she said that I did not know anything. “It doesn’t matter if the Protocols are true,” she said. “Most Arab Muslims believe they are true, so that is the reality you deal with.”

Semite and Anti-Semite

“We are Semites ourselves,” said Mohammed, the association’s president, speaking to me in a cramped office at the Student Center. “How can we be anti-Semitic?” Mohammed seemed a bit old to be a student. He came to Detroit from Egypt, which led to the rumor that he was also with the Muslim Brotherhood. I had no idea if that was true, but he was to become my nemesis for the next three years.

“It doesn’t matter if the Protocols are fiction. Maybe they are, maybe they aren’t,” said Mohammed, arms waving, gesturing, hovering over me as I remained seated. “But you cannot deny that many of the prophecies in this book have come true. Jews run the financial systems.”

“Prophecies,” I thought. “Prophecies.” It’s the language of religion used to describe an anti-Jewish invention from the czarist era. I cocked my head a bit like a dog. Mohammad picked up on it immediately. “Yes, prophecies.”

Strangely, my story would be plagiarized by an intern at The Detroit Jewish News, leading to the firing of the intern who was replaced by me. This unexpectedly led to my career as a “Jewish journalist,” and eventually, years later, managing editor at JTA, a Jewish news service. I hadn’t meant these things to happen.

But I was only in college, was learning as I went along, and had not yet had my full immersion into Arab culture with Lamya and her friends. That would come later, and through it an appreciation of how very alike Jews and Arabs were in many respects. At that moment, though, at the age of 19, I thought I knew what an anti-Semite was.

Accidental Jewish Journalism Career

I wrote the Protocols story, which led to my friendship with Lamya, who would change my life in many ways, aside from telling me that I did not know everything. Strangely, my story would be plagiarized by an intern at The Detroit Jewish News, leading to the firing of the intern who was replaced by me. This unexpectedly led to my career as a “Jewish journalist,” and eventually, years later, managing editor at JTA, a Jewish news service.

I hadn’t meant these things to happen. But I felt I was being dragged there by this state of Jewishness that I could not escape. It was a voice that was always there since as long as I had conscious thought. It was sometimes my grandfather’s voice, other times I interpreted it as God’s. It could not have been my own, since there were obviously forces outside myself at play. I was convinced of it.

This voice led to the illusion of conviction and confidence and how very convinced I was that I was right. It’s how I stoically endured, expressionless, when the entire Arab student body showed up to a public forum to denounce my application to be editor-in-chief of my college newspaper. It’s how I handled the humiliation when Abbie Hoffman, himself, denounced me at a campus rally as representative of all that was wrong with the youth of the 1980s.

The tics of my early childhood had morphed into rigid thought in college. Yet, the feelings of being out of sync with my peers, of having another being travel with me, forcing my muscles and my brain synapses into rigid rituals, were still there in more disturbing forms. The tics, the habits, even the waking sleep paralysis and night terrors I had mistaken for God much of my life. What else could they be? But by 1985 I knew that it was a flaw in me. The voice was more than an impulse. It was much more dark, persistent, life-swallowing than the narcissism of youth.