My Notes From the Birth of Birthright Israel

20 years ago, there was a great fear that young Jews, facing no anti-Semitism, were losing connection to Judaism.

When I was managing editor at JTA (1999-2001) I covered the birth of Birthright Israel and other issues involving younger Jews searching for connection to Judaism. Strangely, at the time, there was a fear that an end to anti-Semitism would further erode the tenuous connection young people had to Judaism.

Folks like Birthright Israel founders Michael Steinhardt and Charles Bronfman, leaders at Hillel, and others were actually bemoaning the fact that young Jews were not having to deal with anti-Semitism, as their parents did, so they’d have to bring young Jews together in other ways.

Much of the Birthright story I wrote was left on the cutting-room floor, so here are some more details from my notes. Today, I find them especially interesting. I’ve placed some text in bold now for emphasis.

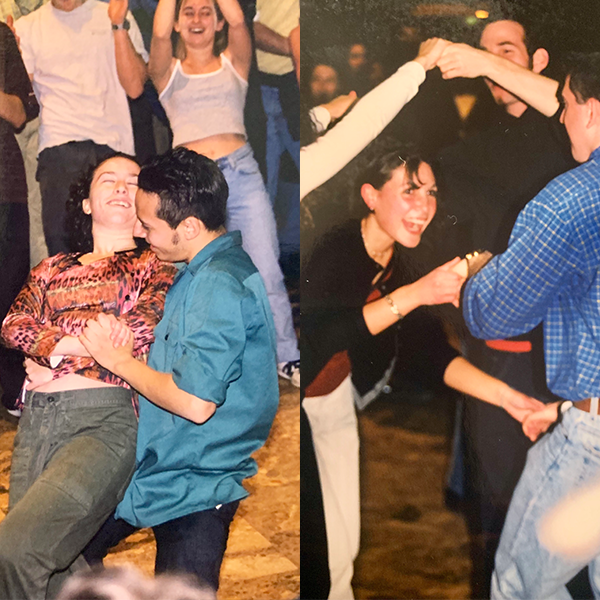

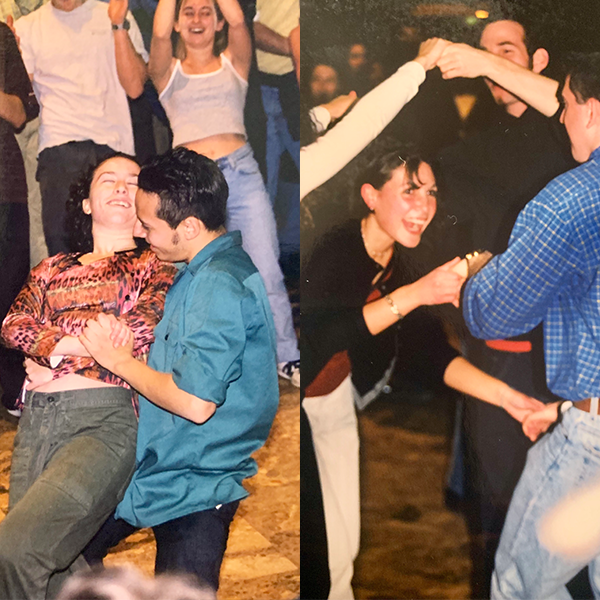

Tears welled up in Michael Steinhardt’s eyes as he was given a raucous rock-star greeting Saturday night by roughly 4,000 grateful young Jews who packed the Binyanei Ha’umah convention center in Jerusalem. He and fellow Jewish philanthropist Charles Bronfman were joined by Israeli Knesset Speaker Avraham Burg and other Israeli officials in welcoming participants of Birthright Israel, many of whom had already spent a week in the Jewish State as part of a program to provide Jews between 18 and 26 with free trips to Israel.

Steinhardt told the young Jews that the price of Jewish success and a retreat of anti-Semitism has been a weakening of Jewish ties. He called on the Birthright participants, most of whom are unafilliated, to rise to the task of “renewing Judaism.”

Prime Minister Ehud Barak, who was in the United States talking peace with Syria, sent a videotaped message in which he promised full participation of young Israelis in the Birthright program to enhance the bonds between them and their Diaspora peers. Burg told the group that they are “the first generation that can ask the question, ‘Can the Jewish people survive without an external enemy?’ ” The Knesset speaker looked at the young faces and said that seeing Israeli and Diaspora Jews together makes the Jewish people “complete.”

If you push the students who say they are culturally Jewish, and ask them to tell you what it is, ask them to tell you about their story, you don’t hear a lot of culture, you hear a lot of vagueness.

I tend, in my dourest moments, to consider both the Reform and Conservative Jews as historic accidents in the 21st century and suspect before the end of this century they will have disappeared.

The hotel ballroom was filled with men and women who have dedicated their lives to using their voices. Yet at that moment, not a sound was heard. The grumbling during the next 24 hours was quiet and largely “off the record,” and worrisome. “Ignorant,” is the word one rabbi used to describe the philanthropists.

As I talk to Jewish thinkers, they tell me that even Tikkun Olam is bad for the Jews, or that “cultural Judaism” still means death to Jews. Most of them say that this notion of Judaism without God or synagogue is not sustainable. I’ve been told this by rabbis of all denominations for thirty-five years. Yet cultural Judaism endures.

Today, as I interview people whose connection to Judaism is strengthened through the rise in anti-Semitism, I argue that, while we’re all together feeling united as Jews as anti-Semites from all political points of view close in on us, let’s also revive the discussion of what it means to be a Jew. When faced, again, with existential crises, now is the time to talk about what being Jewish is and what it means. In fact, it’s the perfect time, because people who never thought about their Judaism before are now constantly reminded of it by anti-Semites.