Remix Judaism, But the Song Remains the Same

Author: Find personal meaning in Judaism if it’s tied to a ritual that can be passed on to the next generation.

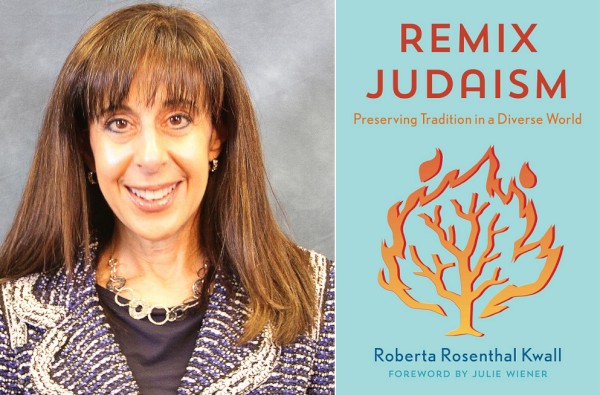

In my latest feature for Publishers Weekly, I interviewed Roberta Kwall, author of Remix Judaism: Preserving Tradition in a Diverse World. Kwall’s book answers, in part, a question I asked in a JTA piece I wrote last summer. Now that Jews are finding their way back to “feeling Jewish” due to a rise in anti-Semitism, how do we get them back to “being” Jewish? It’s in the “remix.” You can read “the writers’ cut” of my JTA piece here.

And, in the tradition of offering my blog readers slightly different versions of my stories, here’s the raw, unedited version of my feature on Roberta Kwall:

When sound engineers remix music, they break it down into its component parts and then recombine the pieces into something that may still be the original song, but with subtle differences. Maybe they’ll add a heavier bass line for dancing or make that screaming guitar solo pop. Well, take that idea and apply it to Judaism. Add an emphasis on lighting the candles on Friday nights, or decide to keep kosher, or follow any other Jewish ritual. Just one of them. And what you have is something author Roberta Kwall calls “Remix Judaism.” It’s still Judaism, it’s still the same old song, but with personalized features. And, more importantly, it is tied to Jewish ritual.

“There’s a lot of interest in creativity,” said Kwall, author of Remix Judaism: Preserving Tradition in a Diverse World (February 2020, Rowman & Littlefield). “But how much of it is being connected to ritual? There’s so much activity in the American Jewish community, but very little, in liberal circles, is being focused on the ritual and how to make the ritual meaningful.”

In other words, any “remix” of Judaism has to be recognizable as the same old song even when there are added emphases or flourishes.

This is a point that Kwall began to make in her previous book, The Myth of the Cultural Jew (2016, Oxford University Press), where she argued that secular Jews who claim they are “cultural Jews” only don’t realize that Jewish culture has its basis in Jewish law. “The law and the culture are inextricably intertwined,” she said.

Kwall, a law professor at the DePaul University College of Law, did her initial scholarly work in the doctrine of moral rights, under which an author has the right to preserve the integrity of their work and not have it compromised against their will. So, the question she kept asking was how much you can change the pages of a book, a piece of music, and still consider it the work of the author.

“I woke up one day and said, ‘Oh my gosh, you can ask the same question about Jewish tradition,'” Kwall said. “How much can it change and still be Jewish tradition?”

For example, Kwall said, her daughter once told her: “I just think, Judaism is about being a good person.” This is part of what many liberal secular Jews call Tikkun Olam, or “repairing the world.”

“Well, I said, sure. Tikkun Olam is a part of Jewish tradition, of course. But if you’re going to just take that and divorce it from ritual, you need the ritual as well,” Kwall said. “And that’s really what my book is trying to show. You need the ritual. It doesn’t mean that you have to practice the ritual in the way that theologically observant Jews are practicing it. You don’t have to practice it to the same level or with the same or the same amount. But you have to be doing some ritual.

Tikkun Olam is a part of Jewish tradition, of course. But if you’re going to just take that and divorce it from ritual, you need the ritual as well. And that’s really what my book is trying to show.

And sticking to the ritual is important, she said, because that is how you transmit the ritual to the next generation. “That’s really what my book is trying to do,” she said. “It’s trying to show how you can tap into personal meaning in order to get yourself to perform the ritual, and the importance of consistency.

Kwall gives the example of lighting Shabbat candles every Friday night because the candle holders might have belonged to a deceased relative; or decided to refrain from eating pork out of concern for the conditions under which farm pigs live. Both of these actions conform to Jewish custom or law, even if they did not come by these rituals or actions for Jewish reasons.

Kwall said she felt her book was necessary because as she speaks at synagogues and listens to concerns over whether their kids will continue Jewish traditions, she hears very little about how the Jewish community arrived at this place. Instead, the dialogue in Jewish communities have become polarized politically between right and left. Conservative or liberal politics, though, does not transmit to younger people in a way that sustains Jewishness. To Kwall, that is “unacceptable.”

“To me, there’s just so much beauty in Jewish tradition, that it can’t be the property of just any one sector of the Jewish community. And it shouldn’t be. But I think a lot of people don’t really have enough guidance for how to own it and how to make it their own.”

Kwall hopes her book can trigger a dialogue in Jewish communities over transmission of ritual to younger generations. No matter how the rituals are remixed, it will still be recognizable as Judaism.

“Think about how much stronger American Jews would be if every Jewish family were at least coming together on Friday night. If every American Jewish family we’re just sitting down together even for one hour on Friday night with no technology, lighting a candle, saying a quick bracha (blessing) over the wine and talking to one another even for an hour., Think how much thicker our cultural religious tradition would be here.”