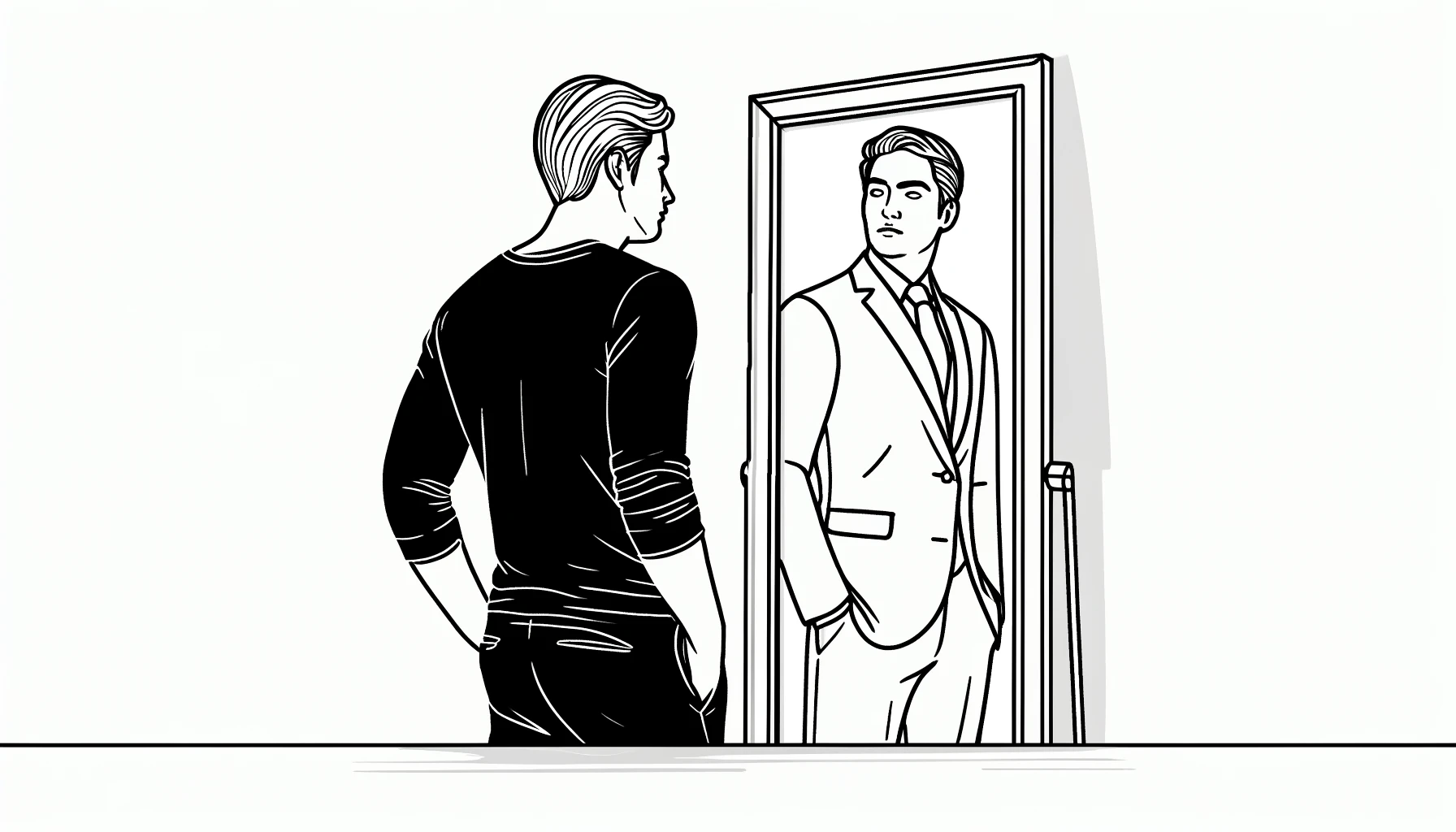

In Naomi Klein’s book “Doppelganger,” she discusses how she’s often confused with conspiracy theorist Naomi Wolf. Klein, a Jewish author known for her anti-Zionist stance, navigates this with the ease afforded to those whose views align with the prevailing anti-Zionist sentiment in the literary community. This contrast is kind of a funhouse mirror of my own experience as I labor on my book, From Outrage to Action: A Practical Guide to Fighting Antisemitism. Somewhere out there, perhaps, is my doppelganger who finds the literary gates swung wide open because he echoes the anti-Zionist words that publishers and literary agents want to hear.

“My life and career would be a lot easier if I just announced that #AsAJew, I denounce Zionism, and that I have a manuscript telling the story of how I cannot support the apartheid, settler-colonial, white European project in ‘Palestine,’ I wrote in my recent op-ed for The Algemeiner. “Phone calls would be returned, emails would be read, and literary agents would compete in bidding wars to see who could give me the biggest advance.

“Unfortunately, for my writing career and reputation, I don’t believe any of these things.”

The situation within the literary community highlights a deep-seated issue that extends beyond mere business decisions; it reflects a troubling cultural bias that affects the core of Jewish identity in the literary world.

“Even Jews who are not Israeli and don’t write about the Middle East are having doors slammed in their faces,” I wrote. “Word in the industry is that editors, agents, and publishers just don’t want to hear from Jews now. There’s a great deal of fear among Jewish authors. They are losing contracts, calls are not being returned, and books are canceled because of a perception in the industry that there’s not really a market for Jewish voices, except those of the #AsAJew anti-Zionist variety.”

In my op-ed, I highlighted the rejection and challenges that Jewish authors face. Despite such discouraging experiences, we, as Jewish authors, are increasingly determined to confront and write about Jewish issues. We’re countering the prevailing anti-Zionist narrative through online campaigns and public letters, including an Open Letter on Antisemitism, which I proudly signed.

The Jewish Book Council is also taking action by collecting data to assess whether these are isolated incidents or indicative of a broader trend. In many cases, the literary community, which should champion diverse perspectives, instead leads the charge in silencing them, failing to engage critically with the complexities of Jewish and Zionist experiences.

Addressing these concerns in an interview for The Times of Israel, I expressed the urgent need for Jewish voices to rise: “Now, more than ever, it’s time to make our voices heard. In fact, I’ve spoken to Jewish authors who decided that they will write about Jewish issues more now than they would have otherwise. The answer to the silencing of Jewish voices is to make our voices louder.”

Out in the mirror universe, my anti-Zionist Jewish doppelganger finds acceptance by echoing the anti-Israel words the literary community wants to hear. This highlights the critical need for us, as Jews, to be comfortable with who we are and to speak out with our authentic voices. If we don’t, these distorted doppelgangers will speak for us, perpetuating narratives that misrepresent our true identities and experiences.

Chag Sameach and Happy Passover to those who celebrate.