To study Judaism is almost like studying physics. Everything seems to follow straightforward rules, until you take a closer and closer look and you see those bizarre quantum effects. Jews have no pope, no central authority, so not only does practice of Judaism vary greatly, so does the Jewish concept of God.

Now, add in the Jewish philosophers (as opposed to theologians), and the Jewish concept of God can vary even more. So, what is the Jewish concept of God, exactly? That’s the heavy question for which I sought answers when I interviewed Andrew Pessin, professor of philosophy at Connecticut College.

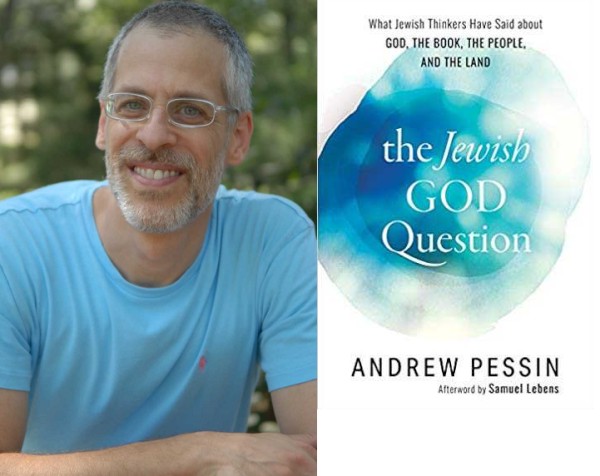

He had just finished a book called The Jewish God Question: What Jewish Thinkers Have Said about God, the Book, the People, and the Land. He put together a set of questions using different voices throughout history—everyone from the secular Zionist leader Theodor Herzl to Chabad’s Rabbi Sholom Dov Baer Schneersohn.

The result was a great collection of writings from Jewish thinkers throughout history.

In this article for Publishers Weekly, we discussed what Jews think about when they think about God. But, here is the “writer’s cut” version, with more questions and answers than PW can fit. Thank you to Andrew for a great interview.

Howard Lovy: Everything seems to follow rules when you look at Judaism, but the closer you look the more chaotic everything seems. What was your goal in putting this book together?

Andrew Pessin: One is the selfish goal of, I wanted to learn this material. I realized I was becoming an expert on medieval Catholic theology, but it started occurring to me I knew almost nothing about my own Jewish background and heritage. When you’re reading Western philosophy, the Jews are largely excluded from the canon. So I had this kind of awakening a few years back where I said, “What were the Jews saying during all these centuries that I’ve been studying?”

The second is over the past 10 years or so I’ve developed a general interest in spreading the wealth of philosophy to nonprofessional philosophers. I would write a scholarly article on Descartes, and 10 people would read it and, as I like to say, eight of them would ignore it and two would criticize it.

Howard Lovy: When Jews think about God, do they think about a different kind of entity than does a Christian or a Muslim?

Andrew Pessin: That’s a really deep question and it presupposes that there’s some single unified notion of God within each of those three religions. They have really extremely different conceptions of the divine being within each religion. And what I’m discovering — and this is kind of exhilarating for me — is that a lot of these Jewish thinkers end up not only disagreeing among themselves about the nature of the divine being, but end up saying exactly the same sorts of things the Christians and Muslims have said in their disagreements.

A lot of these Jewish thinkers end up not only disagreeing among themselves about the nature of the divine being, but end up saying exactly the same sorts of things the Christians and Muslims have said in their disagreements.

Howard Lovy: Do you approach this subject as a philosopher or a theologist? What is the difference?

Andrew Pessin: Great question. The distinction would be based on the idea that for the philosopher, there are no constraints on what he or she thinks other than sensory experience, historical experience, and reason. In theology, they start off with certain givens and those givens might be, for example, there’s a scripture and that scripture is accepted to be divine in nature. It’s sort of roughly the distinction between reason and revelation, where the philosopher is guided by reason and the theologist — not being irrational or anti-rational — has an additional constraint in his or her reasoning.

Howard Lovy: You put together a really ambitious set of questions through these different voices throughout history. What is God? Is there life after death? Is there a soul? Why are we here? After reading this, will I get a better idea of the answers?

Andrew Pessin: I wasn’t attempting to answer those questions. I was attempting to raise them because in the history of Jewish thinkers, these are among the major questions that they grapple with. You know the famous adage: you ask two Jews, get three opinions. As I like to say about this book, I asked 72 Jewish thinkers and got more opinions than I could actually count. I leave it to the reader to decide in the end.

Howard Lovy: Will this book answer questions about what Jews believe about X, Y, or Z?

Andrew Pessin: It may not give you the definitive answers. You’ll notice that even though Maimonides was certainly the towering figure of the Middle Ages, and arguably the towering figure in the whole history of Jewish philosophy, that doesn’t stop people from disagreeing with him on absolutely every single issue. Maimonides is not the pope and you can quote me on that.

Howard Lovy: Who was the best writer?

Andrew Pessin: Abraham Isaac Kook, the first official state rabbi in Palestine, is just a beautiful poetic mystical writer. It’s so very challenging to figure out exactly what he’s saying and to put it into comprehensible English. I did try to do that in one short chapter in the book, but reading him is really stimulating in a kind of mystical way. So that’s what comes to mind for me.